Orient Yourself

GET STARTED

Taking on a debate topic may seem like a daunting task! --

but there are several things to keep in mind to make it easier.

- First, get comfortable with your topic. Start by determining, if you haven't already, the opposing positions engaged in this debate -- there are many resources on this page to help you (a pro/con database might be a good place to start!).

- As you are getting started, you might also find it helpful to explore current, "popular" takes on the debate, from both sides. News sources can be useful for this purpose. Note, though, that your research should not stop here -- you need to locate solid, empirical evidence to support your position to the extent possible.

- You should also try to understand the history of debates around your issue, because this history will influence how the issue is debated today.

- Remember that it is not enough to immerse yourself in "your" side of the debate -- to construct a strong argument, you must be fluent in both sides of the debate. You should understand the strongest arguments on the opposing side, and be ready to refute them. You also need to be aware of the weak points in your own argument, and seek evidence to strengthen them.

- Your goal is to be as informed as possible -- so leave yourself plenty of time! Brainstorm and consult different types of (reliable!) sources which might fill gaps in your knowledge. There is more information about these resources throughout the guide.

UNDERSTAND YOUR TOPIC

Say for your example that you have chosen to argue:

"The U.S. government should forgive student loans."

Consider:

- Is this specific enough to research? Too specific? Is there anything missing?

- What else do I need to know before I can understand or make an argument about this topic?

- What kinds of considerations (economic, moral, legal, etc.) do I need to take into account?

- What are other words that I could use to talk about this topic?

- What are words that I could add or change to make this topic either bigger or smaller?

DIAGRAM YOUR TOPIC: (optional, but recommended!)

Try diagramming your topic as a brainstorming exercise. This can be one way of thinking through the many different directions and conversations that you might want to incorporate in your arguments.

- Start with the topic, question or argument you are working with.

- Underline the 2-3 main ideas (look for the nouns in your topic or question statement!).

- For each of the ideas you underline, try to come up with at least 2-3 synonyms, related terms or other ways of expressing that idea. write these down -- they will make good search terms as you embark on deeper research.

- Add in related concepts or questions that you may want to consider or search for.

- Identify (and circle or otherwise mark) parts of your statement or question that prompt further questions. Write these down -- these are questions your opponent may raise, that you should work to respond to.

- Identify parts of your statement or question that demand empirical evidence for support. Note these as particular points that you should research!

- Continuing adding as you need and want -- don't be afraid to keep editing throughout your research process.

EXPLORE PROS & CONS:

-

CQ Researcher This link opens in a new window

Weekly reports focused on "hot topic" issues with summaries, viewpoint essays, and further reading.

-

Congressional Digest & Supreme Court Debates Online This link opens in a new window

Available on-campus only. Monthly “pro/con” reports focused on pending U.S. Congressional legislation and Supreme Court debates, with regular updates as issues evolve.

The following websites are also useful and generally-trustworthy sources for exploring the multiple sides of a debate:

CHECK THE NEWS:

Library Databases

Below are listed the main databases available at Holy Cross to locate current magazine and newspaper articles. Note that papers from different geographic areas might treat the same issues differently.

-

Access World News This link opens in a new window

Local, national, and international news, including the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

-

Boston Globe Current This link opens in a new window

Date(s): 1980-present

Text-only articles from the Boston Globe. -

New York Times Current This link opens in a new window

Date(s): 1980-present

Text-only articles from the New York Times. **Blogs are not included.** -

New York Times Current (SGA Subscription) This link opens in a new window

Current access to the New York Times site, including news, columns and more -- courtesy of the Holy Cross SGA. ** To access, create an account with your HC email address. If you already have an account, there will be an option to click-through to log in.

-

U.S. Newsstream This link opens in a new window

National newspapers, blogs and online news sites, including the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Wall Street Journal.

On the Web

Depending on the geographic area involved, you may or may not find many articles in the Holy Cross collections that are helpful. At this point, you may want to venture out onto the web -- that's okay! Make sure to pay close attention to the sources you find, and think critically about how reliable they are. If you're not sure about a source, ask!

Here are a few places you might think about looking:

-

Google Newspaper ArchiveFree, online access to digitized newspapers from around the world, covering a range of dates from 19th century to present. Search or browse an alphabetical list of titles.

-

Newspaper Digitization Projects - ICONA list maintained by ICON (International Coalition on Newspapers) of newspaper digitization projects, organized by both country and US state.

-

Wikipedia List of Online Newspaper ArchivesYes, this is one of those times when it is OK to use Wikipedia as a resource! This page provides a crowdsourced list of online newspaper archives around the world, including information about access. Use the navigation menu to the right to jump to the country/state you're interested in viewing.

Consider Different Types of Sources

The Information Lifecycle helps us understand how information about an event, topic or idea might emerge and evolve over time.

Note that this timeline is just a general sense of the information lifecycle -- the exact timing can vary greatly from one discipline to another!

During your time at Holy Cross, you may find yourself using a combination of both popular and scholarly sources.

A popular resource is a resource for 'popular' consumption -- it has been written so that most people can easily read and understand it. This might include newspapers or magazines, some books, and some journals written for people in specific jobs. While there is usually an editor who checks these sources for good writing and for errors, this is mostly done by a single person rather than a group. Popular articles are usually written by journalists or professional writers, although sometimes they are written by experts on a specific topic.

Scholarly sources are written by experts on a particular subject (for example, a professor or other researcher). They also go through an extra process of review and approval by a group of other experts before they can be published. Usually, scholarly articles are written in 'academic-ese' and designed to be read by other scholars. You will probably find yourself using many scholarly sources in your other Holy Cross classes. However, because scholarly sources take a long time to be approved and published, they are not good sources for current news. Click here to explore the parts of a scholarly article as shown by the NC State Libraries.

How can you tell if you have a scholarly article in your hand?

The chart below compares the characteristics of scholarly vs. popular (non-scholarly) sources:

| POPULAR | SCHOLARLY | |

|---|---|---|

| author | Usually staff writers and/or journalists | Experts on the topic -- usually researchers, scholars and/or professors |

| audience | General public (for "popular" consumption) | Other experts (and students) in the field |

| editing & review | Editor(s); generally concerned with grammar, style, etc., with some fact-checking | Other experts ("peer reviewed"); generally concerned with quality, thoroughness of research, strength of argument, etc. |

| style & design |

Reasonably brief, typically uses colloquial if not informal language. Often illustrated with graphics, sidebars and other aesthetic elements. Sometimes accompanied by ads. |

More extensive in length; tends to be more formal and uses specialized vocabulary. Illustrations and charts are used only when furthering content. |

| goal or purpose | To entertain; and/or, to share general information | To share findings, advance and argument and/or engage with other scholars |

| sources | Few or none; if sources are used, there may not be formal citations. | Typically uses many sources, cited in detailed bibliographies, footnotes and/or endnotes |

| examples | Time Magazine; Sports Illustrated; New Yorker; Boston Globe | Annual Review of Political Science; American Historical Review; Sociology of Education |

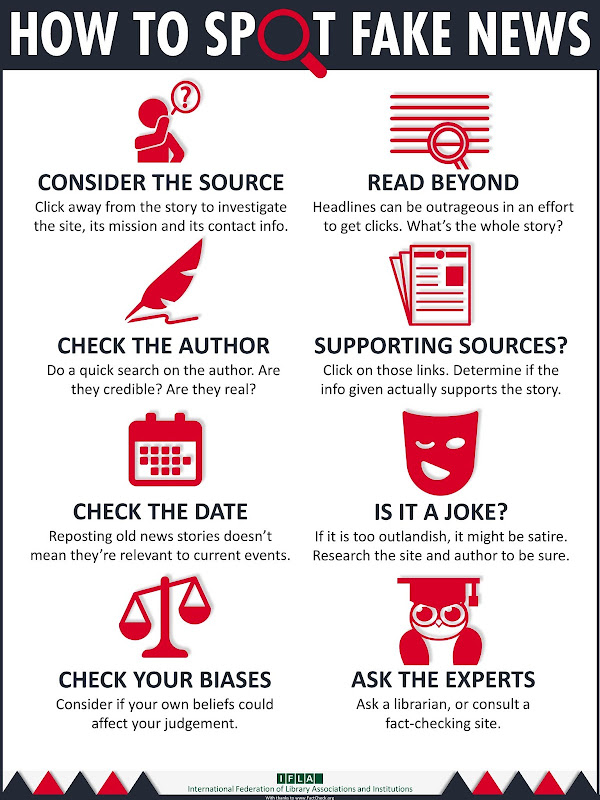

No matter what you're researching or what kinds of information you're working with, you should always interrogate your sources.

Lateral Reading is a more nuanced technique of evaluating websites and other kinds of sources.

While the questions on the previous page are a great place to start, sometimes you can't answer them completely -- or, sometimes, they don't give a complete picture of the information you are looking at.

The video below explains what lateral reading is, why it's important, and how to do it.

We've all heard the term "Fake News" -- even when information isn't blatantly or deliberately false, it's still a good idea to check the facts (see the video on Lateral Reading for more).

Not sure where to look? The page below offers some helpful resources for checking 'fact's of all kinds, from data to images:

-

11 Non-Partisan Fact-Checking WebsitesCompiled by J. Greller, "A Media Specialist's Guide to the Internet" [blog], Aug 31, 2020